Everything I Needed to Know About Managing Adult ADHD I Learned From Star Trek

I am the voyages of the Braincraft Gray. My lifelong mission: to eke out good life and well-thought-out decisions. To boldly go where my brain has never gone before… (Cue theremin and whooshing spaceship noises!)

There’s one phrase I think I hear more than any other from my fellow late-diagnosed ADHDers:

- “I’ve always felt like I’m living in a world that was not made for me.”

Something about that phrase pinged in my imagination: a world that was not made for me. A world where I felt alienated…struggling in a hostile environment…exhausted from trying to accomplish my tasks and never knowing what new obstacle or even attack might be coming next…

Wait a minute. I know this trope. I’ve watched, read, and gamed riffs on this story for my entire life. Imagine some ethereal, high-pitched pinging tones, with a rising trombone fanfare underneath…”

I am the voyages of the Braincraft Gray.

My lifelong mission: to eke out good life and well-thought-out decisions.

To boldly go where my brain has never gone before…

Cue theremin and whooshing spaceship noises!

Just Because It Wasn’t Made for My Brain Doesn’t Make It Hostile

In this metaphor, the neurotypical world we live in is like an alien planet—its rules, expectations, and environments weren’t designed with ADHD brains in mind.

Except remember, in most of the planets visited by the crew of the Enterprise, they were the aliens. The worlds weren’t specifically created to harm them*. They were simply visiting, to learn about “new life and new civilizations”.

Think about that reframe from a neurodivergent point of view. The “local” customs of the neurotypical world — things like eight-hour days, the ability to stop scrolling social media, just doing the next thing on your todo list — these are strange and, dare I say it, fascinating.

Often the entire episode is about some cultural custom that the crew has to learn to understand. They don’t (usually) say “Oh no, we’ve been wrong about how we do it — we should change to be like them!”

They learn, they adapt, they respect these other customs — even adopt them if they spend a lot of time in this other culture. But they rarely reject who they are intrinsically, whether as individuals or as the Federation.

Part of the fun of the Star Trek mythos is watching them accomplish their mission in spite of feeling overwhelmed and disoriented in worlds that were not “built for them.” Often this is because of the technology they have, and that’s another reason I love Star Trek. I am literally typing this article about the series on technology that was inspired by it**

The primary technology they use is their starship, that carries them and provides the tools and protection they need to interact with the rest of the universe. Thanks to the way our bodies evolved, we all have the illusion that the bowl of electrified jelly at the top of our spine is what directs the rest of our body, kind of like the crew sits on the bridge.

Can we map a starcraft metaphor to the metaphor of our conscious brain — especially if it’s ADHD?

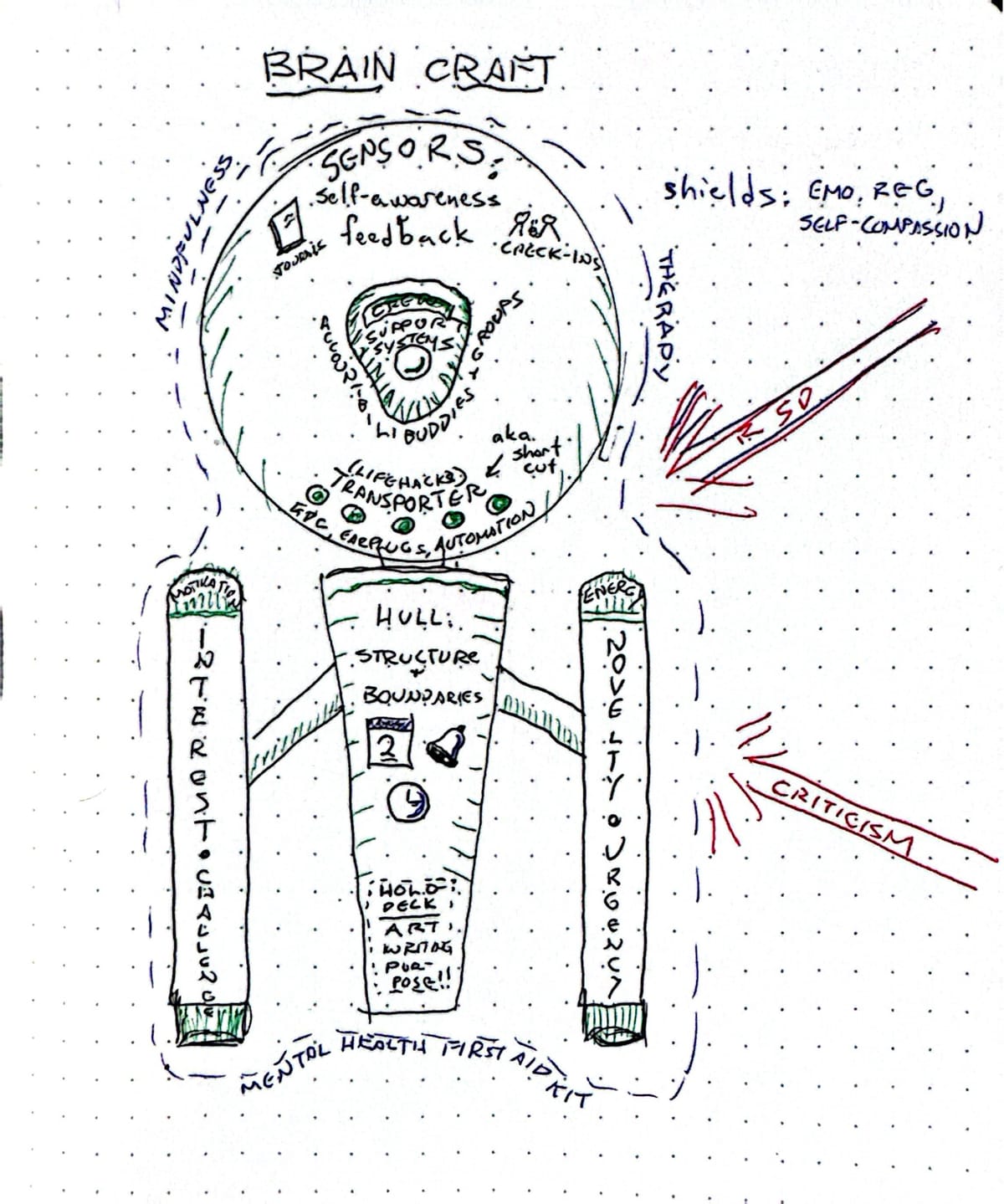

Let’s pretend we’re in a little shuttle craft touring the dry dock at ADHD Base Barkley I’ll take you on a quick tour of the Braincraft Gray’s Matter — my personalized ADHD toolkit I’ve been building for the last three years, ever since my diagnosis changed my fifty-plus-year mission.

The Hull (Structure and Boundaries)

The outside of my braincraft is made of the externalized structures and routines that protect me from the chaos of the neurotypical world.

Over here is my Apple calendar, which interfaces with the braincraft of those most close to me as well as my boss — er, commanding officer. Notice how it is reinforced with Apple Reminders and utilizes a latticework of “work” “rest” and “play” sessions.

This current hull is a relatively new design, after almost two decades of using Google calendar. This worked well until the Ferengi bought the company and I noticed how many ways it was profiting off my information without my consent.

I tried other systems and apps, but finally solved the cursed problem of personal knowledge management by accepting an uneasy alliance with Apple.

Much as the hull of the USS Enterprise protects the crew from the vacuum of space, this core structure of calendar, task, and time management protects me from the overwhelm of unstructured time as I navigate my universe.

The Engines (Motivation and Energy)

I can see you admiring my nacelles, and I appreciate your restraint in not just coming out and asking. That’s right, these are some of the newest additions to the Matter. Unlike neurotypical brains, which are fueled by a mix of do-ilium in a responsibilitrate matrix, the fuel that makes my brain move is a proprietary mix of noveltite and urgentonium moving through a Fascination field.

Yeah, it is pretty cool that it’s one of Spock’s favorite words. I don’t think that’s a coincidence.

That field is the real key — even before my diagnosis, I knew that the novel and the urgent would get me going. It was when I figures out how to become fascinated with a goal that I began to amaze people — especially myself — with how quickly I can get there.

Heck, I made the Kessel run in less than twelve—oops, sorry, wrong universe.

A hyperfocus-enabled braincraft is a pretty powerful vehicle. It can move huge projects like yearly reports, open space events, or unrefined Medium article ideas by breaking them into smaller chunks that are devoured by supercharged cognitive flexibility and Odysseus-level problem solving.

One of the benefits of getting my own diagnosis was discovering that my braincraft’s engine can be augmented if there is another braincraft in the vicinity, even if they’re focused on a different goal. It’s called “body doubling”, because if you have more than a couple you run into the Three Body Problem (oops, slipped on the metaphor again, sorry, Mr. Chiang).

Yes, I have tried the the “gamification” upgrade to see if it would improve the output of my braincraft, but it actually reduced my motive action — motivation, if you will. It turns out that little eight-bit game avatars and chains of x’s on a calendar just don’t work as well as simply pointing Gray’s Matter at a goal and saying “Hey, I bet you can’t get there…”

The Shields (Emotional Regulation and Self-Compassion)

Yeah, I know — the Gray’s Matter does look a bit beat up. Can you believe it, this braincraft traveled the neurotypical galaxy for over fifty years before ever getting an effective shield?

That’s right — no protection from the emotional blasts of rejection sensitivity, criticism (both actual and perceived), or just plain burnout.

Now, though, there’s a layered array of mindfulness practices such as breathing and presence heuristics (”I am here, now, doing this thing, in this place, and I am aware of everything around me.”). This has included a few years of therapy and partners and friends who know when and where to pull out my "mental health first aid kit" for tough days.

“Focus shields!” is a common order heard when the starship Enterprise is under attack. My braincraft shielding can also be configured to meet the needs of a particular attack — forward, for example, when I’m going to be networking with a lot of people, or drawing power from one area to make them stronger.

Oh, you want an example? Let’s see…how about this.

If I’m starting to feel peopled out at a fundraising gala, I may ease up on the inhibition that is helping me resist the raspberry cheesecake at the buffet — or vice versa, if a breakfast networking events has unlimited free custard-filled bismarks (a known flaw in my shielding), I may limit my energies to strengthening my ties with people I already know rather than spend the extra effort to meet new people, because of how much won’tpower I’m using to resist gorging on the donuts.

I also have auxiliary equipment for situations like that — for example, a challenge coin in my pocket is a great unobtrusive fidget that doubles as a spoon regenerator.

(If you’ve read this far and are not familiar with spoon theory, it’s definitely something you should google. Most ADHD braincraft their allies run on Spoon Theory.)

The Sensors (Self-Awareness and Feedback)

One thing that Gray’s Matter has always been good at is exploration. In the absence of good shields for so long, the ability to gather information about the environment and needs of a given situation has served me well.

I use many tools for this, from mnemonics like the OODA loop (observe, orient, decide, act) to Daily Pages and interstitial journaling. I’ve also found immense benefits from simply checking in with friends and colleagues, not necessarily about an issue or goal but just to talk about how we’re doing — energetically, emotionally, physically, whatever. Getting this kind of feedback from trusted allies can be invaluable for identifying what is working and what is not — but it’s essential that I keep my sensors open. If I’m layering on a filter of imposter syndrome or defensiveness, my sensors are not going to do me any good.

My Crew (Support Systems)

While it’s certainly not perfect, one of the reasons I love Star Trek more than most other fiction is that there is usually less focus on the “individual” and more on “teamwork”.

No spaceship runs on its own—it needs a crew, and whether you’re a secret agent in Section 31 or a yeoman on the Lower Decks, the emphasis in the stories is usually some variation of you are not alone.

Gray’s Matter has a had the benefit of many capable crewmembers, including friends, family, therapists, teachers, in-person and online communities who mad me feel understood and supported, even — especially — when I couldn’t understand or support myself.

I had an accountability partner even before I knew I had ADHD, and have both found and formed ADHD support groups online and at local libraries. It was a therapist who first suspected I had ADHD, and just as Captain Kirk has Spock, McCoy, and the rest of the bridge crew, my closest family and friends make me feel like they will have my back no matter what — even, as in so many episodes, they aren’t quite sure I really know what I’m doing.

The message is: I don’t have to navigate the neurotypical world alone. The proof: my fellow ADHDer and friend Karl reviewed an early outline of this article, and said it was worth writing.

The Transporter (Taking my Braincraft to Strange New Worlds)

The transporter is a kind of shortcut—once a starship gets you most of the way there, in friendly environments it can just beam you down, no spacesuit or shuttlecraft necessary. It helps you bypass obstacles and get where you need to go.

My transporter is the internet.

Simply put, I can be “present” in a variety of environments, learning, exploring, interacting with the inhabitants of other braincraft, without having to actually physically travel there.

Like the Enterprise’s transporter, sometimes it doesn’t work so well — low signal strength causing errors, or even time-traveling lapses in asynchronous communication. Sometimes I can even cheat and use the transporter to double my presence — say, attending a board meeting and a lecture at the same time.

While this is usually not recommended for any braincraft, neurotypical or otherwise (multitasking is a myth), what it really means is that I can create my own accommodations while I’m present — using noise-canceling headphones, standing and pacing, occupying my hands with a fidget toy or sketchpad, or just keeping my brain stimulated enough to actually give the board meeting the focus it deserves without wandering off.

The Holodeck (Rest and Recreation)

I mentioned one of the biggest powers of Gray’s Matter is the ability to get to goals via hyperfocus. This is a flow-state that bypasses time, space, and the physical form to achieve more work in less time than anyone would believe possible.

It’s also takes incredible energy. Coming out of hyper-focus can deplete your stores of dopamine and serotonin (not to mention water, food, and your cat’s goodwill) for the rest of the day, if not more.

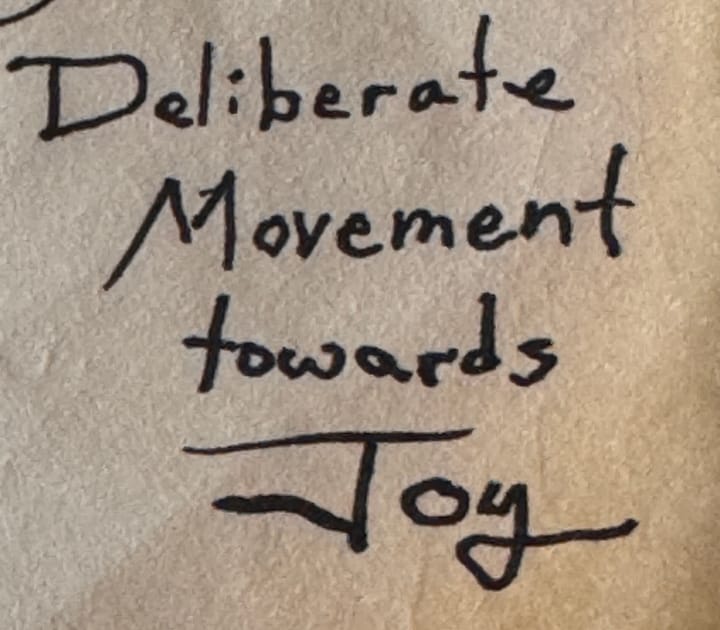

The holodeck is more than just a fun space — it’s a space where I can take a deliberate rest, doing the things that will recharge my executive functions through play.

It’s a little dangerous — the line between play and project is easy to blur, and before you know it you’re trying to monetize your cat-hair yarn-spinning hobby that used to be so peaceful. For my ADHD braincraft especially there’s a tendency to jump ahead to what a creative outlet could be, rather than what it is: a place where I can just do something I enjoy, with no expectation of an outcome besides spending time doing it.

My primary holodeck programs are papercraft, hand lettering, action movies, playing ’80’s pop on the ukulele, or binge-watching Korean crime drama.

It’s hard sometimes to keep it tuned up as a space for exploration and joy rather than work and ambition. Much like the Enterprise’s holodeck, more than once a casual diversion has evolved into a life-engulfing entity.

But like them, I keep my holodeck — because having a place where I am not working is an essential part of working better.

Why the Star Trek ADHD Metaphor Works for Me.

OK, I think I’ve made the point. I am already experiencing pre-publishing rejection sensitivity with the idea that no one else is going to relate to this, Gray ( except my friend Karl, who read an early draft and said ”Yeah, that’s kind of interesting”).

But I’m finding that the more time I spend with the metaphor, the more benefit I get from it:

It might sound weird, but it’s actually empowering in a way. It gives a structure and mythos to my everyday. Instead of feeling like my brain ain’t right for this world and that ADHD is a disadvantage, this metaphor positions it simply as the way I am as I navigate environments that were designed for brains similar to but not quite like mine.

(Kind of like the way 90% of the aliens Star Trek meets are basically humanoids who stopped by makeup on their way to the set). My brain is not broken—it just requires some extra equipment to do things in different environments.

It’s also a flexible model, both for me and for others. Every starship crew adapts their equipment and their roster to meet the needs of the challenges they come across; and the Star Trek universe itself has a huge diversity of characters, strengths, and weaknesses in their characters and missions. Janeway, Kirk, Burnham, and Sisko are all captains — but with very different characters, which I can use as inspiration when faced with my own challenges (heaven help you if I’m having a Janeway day, though). And if the metaphor/model resonates for someone else, they can adapt it to their own needs and strengths.

I think that’s one of the best things about this whole idea. There’s no specific studies that show a greater prevalence of ADHD in science fiction fans, but I know that sci-fi conventions and fandoms are some of the places where I have felt the most at home and myself (with some exceptions).

Don’t Overthink It.

I’ll be honest: this metaphor became a hyperfocus for me pretty easily. I enjoyed doodling over starship blueprints in my notebook, imagining “away team” ADHD spacesuits and trying to figure out what a Klingon ADHD coach would be like.

But it’s only useful if it helps me get through my day moving towards the things that I think are important, or if it’s a place to rest rather than escape.

And maybe you’re one of those who thinks the whole Star Trek phenomenon is overblown, and prefer another mythos like Wheel of Time or Star Wars.

You’re wrong, of course (my unbiased completely scientific opinion) but hey, you do you. Humans are narrative creatures; whatever gets you through the day with the least amount of damage is a good thing.

That being said, I’m curious: what stories do you tell yourself about ADHD? What fictional worlds and characters have resonated? And is there any way you can map them to your own life to provide a little more support, a little more energy?

Make it so.

* Well, most of the time. Certainly there were beings (and technology) that created worlds specifically to make life hard for the crew. Isn’t it great that that’s fiction, though?

** The iPad mini, in this case, but there are many, many other examples of things that were fiction on the series that we now accept in our everyday lives.

Comments ()