I'm Not Time-Blind. You're Time-Delusional.

Things you learn in moments of extreme grief, part one.

The funeral-industrial complex is real.

In a way, I'm thankful for this. It gave me something to focus on, a set of tasks and tiny quests to fulfill rather than simply drowning in the grief that accompanied the passing of my youngest daughter, Dani.

I've been very fortunate that as I've worked with two different funeral homes (the body had to be transported) as well as many distant family (and ex-family) members, we've all pretty much pulled together and helped each other through. My oldest daughter just ordered the catering for the funeral service. My middle daughter is coming over to help me edit a video of our memories of her. My ex-wife and her boyfriend are arranging for the body to get on the plane in Aurora, and Dani's twin is going to be in Milwaukee to escort it* the rest of the way.

There's a recurring theme I keep hearing during all these meetings...

- "What day is it again?"

- "Wait, it's (insert time of day) already?"

- "This feels like it's taking forever, how has it only been fifteen minutes?"

It took me a while to realize: these are all things I usually say. And then it hit me:

They're all experiencing time blindness.

Somehow, this traumatic event has disconnected them from their normal (aka, neurotypical) experience of time. Everything is in a hazy state of now-ish, and while we assign events to dates and times in the future, they have as much resonance to our present as saying "Hey, I'll call you at half past green perspicacity with sour beetles."

Here's the thing: traumatic events like death tend to focus you on the essential – one might even say, the real.

And that construct of time that is so prevalent in our culture absolutely collapses in the face of a reality such as death.

It's obvious in the detritus of a life.

I've been time-traveling through this whole experience.

When I went into her room in Aurora, to help sort through her things, I found a letter I'd written her. I opened it, unfolding the letter-locked nerdy stationery, and was puzzled by what I'd talked about in the letter. Because I didn't get into fancy folding letter-locking until COVID...and this letter was dated 2015.

But the paper was crisp and new as if I'd sent it yesterday.

I have our family photos in a jumbled disarray in a box, and going through them was like bouncing from era to era like the Outlander. Here she was, a teen working at the Ren Faire. Then she was wearing a matching toddler dress with her twin. Then she was swinging a bat at a piñata at her 10th birthday. Then on stage with her friends at Proud Theater in high school.

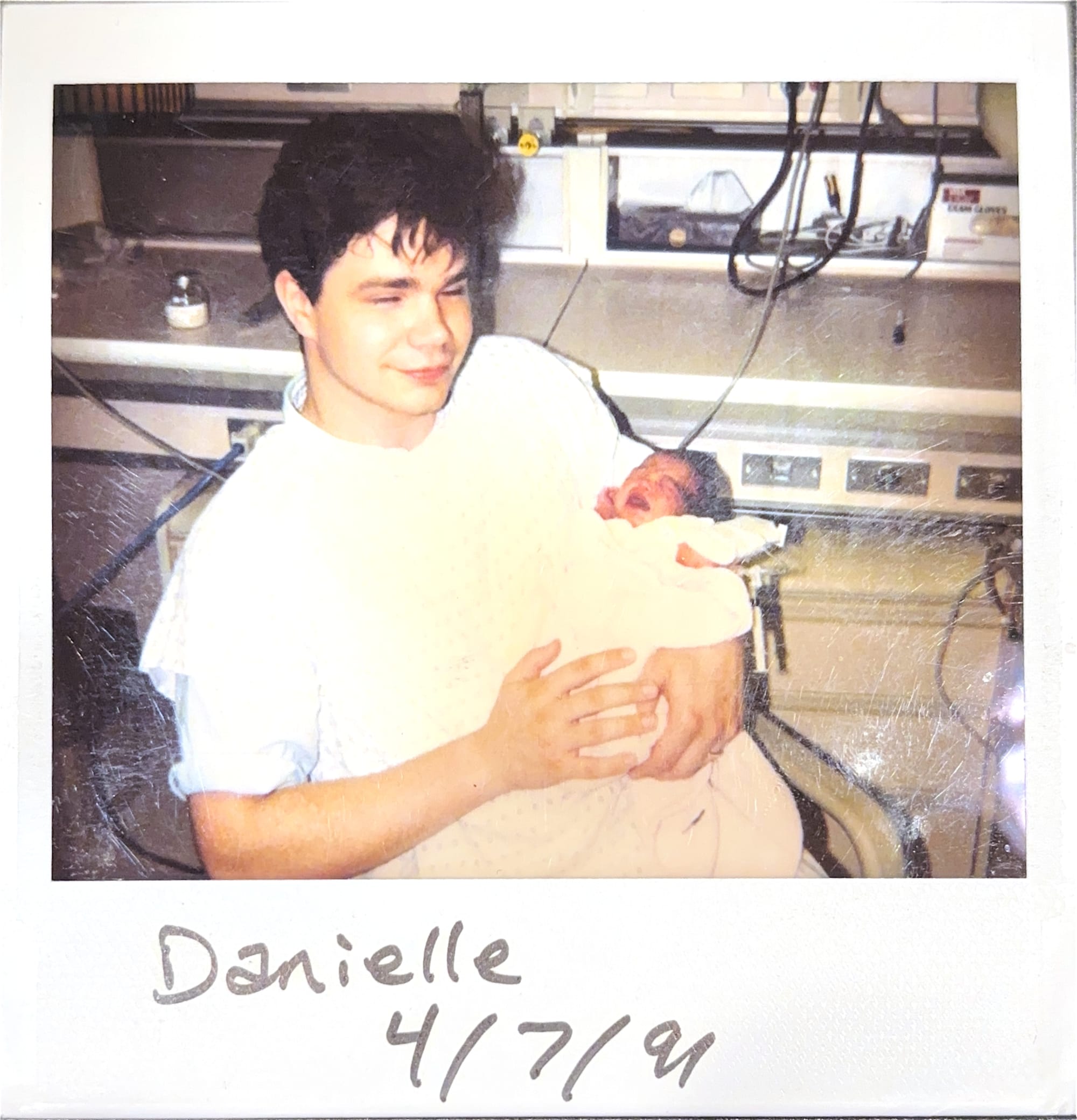

Then there was the polaroid dated one day after she was born, where I'm bleary and tired from watching the difficult delivery but holding my five-pound two-ounce daughter.

That one broke me. I can still feel that time as if it was now. In fact, I wish I couldn't, because it makes it very difficult to write about.

I wonder if it's harder for those more used to neurotypical time to go through this kind of thing? Maybe since I'm used to not understanding time viscerally, I'm insulated a bit from the shock?

A part of me wants to mount the ramparts, waving a flag shouting

"You see? It's all made up anyway! None of that timey-wimey stuff is real! You're all just sharing a mass hallucination!"

But I won't. Even though, if I did, I know that my deceased daughter would smile and laugh and say "Oh, Dad..."

It does help to frame it like that, though. Rather than feel like there's something wrong with me for not really being able to tell the difference between "just a second" and a half an hour, or to really understand how two weeks ago Monday feels, I can instead feel like maybe my own perception of time is a little more close to reality than the neurotypical ideal.

And that will help, in a way, because when people say "Eventually, it will get easier," I can sometimes convince myself that "eventually" is right around the corner.

*yes, "it", I've found that while I don't have any concrete beliefs in afterlife, I am 100% sure that the body that remains is not Dani. I don't argue with those who feel otherwise, I simply know how I feel.

If you're reading this on ADHDopen.space, it's FREE! Sharing it is one way to help support my work.

You can also get inside access to discussions, topics, and previews of my Executive-Function-Externalizing makes, by signing up for a membership.

Comments ()