Not everything can be blamed on ADHD.

But more than you think: a case study.

One of the reasons the internet is saturated with ADHD content is that along with improvements in the diagnostic methods there has been a huge amount of communication, research, and shared experiences that reveal challenges far beyond the “I forget things and get distracted easily” trope.

The Curious Case of the Recurring Argument

For example, my partner Natasha and I love each other very much, but for all sixteen years we’ve been together there has been a certain type of recurring fight. For me, it looked something like this:

- We would disagree on something (often something minor, like “Where should this chair go?”

- My brain is very good at and used to exploring possible outcomes and finding reasons why one might be better than another, so I would start to list them. I’ll list the good options, the bad ones, and all the reasons for and against, usually very fast because I am convinced that if I just give Natasha all the information, she will obviously agree with me and we can move the couch and get on with our lives.

- Natasha would listen and respond to the first minute or so, but even as I crafted my beautiful structure of reason and possibility I would see her disengage from the conversation, sometimes going beyond monosyllabic responses to just staring at me, and when I stopped, shrugging with a tired “OK.”

- I would feel both resentful and guilty, because I absolutely don’t want to be the kind of partner who bludgeons someone into agreement through words, but also I hate feeling like I’m being ignored. I’d begin the list again, phrased slightly differently, spoken a bit louder, perhaps with some interpretive dance thrown in…and same reaction.

We learned to live with it…sort of.

It happened often enough for us to sometimes be able to see it starting, to sometimes avoid it, sometimes find a way through it…but it never really got better.

Then, a few years after my “combined type” diagnosis, Natasha got her own diagnosis: Inattentive type.

The doctor explained this as basically a funnel, but for information: there was no problem processing information once Natasha had it, but the mechanisms for taking it in were narrower than the neurotypical world was designed for. Her coping mechanism for when things got too much tended to be withdrawing and shielding herself from whatever form of overstimulation there was, to sort it out later. This had worked well — she’s an executive at her work now — but it had been a very difficult trip to get there.

Like me and most other late-diagnosed adults, Natasha felt the anger, the grief, the feeling of lost opportunities and needless struggle she’d had throughout her life as her parents, teachers, friends, partners, and herself had acted as if her brain didn’t work that way and blamed her for not being who she is not. (note: Natasha also was given review and editorial control of this article before publication ).

But there was also one very useful thing that came out of her diagnosis: we figured out why we fought.

And we lived happily ever after.

Well, mostly. I mean, look at the world around us in late 2025? Due to events both public and personal, this has probably been the hardest and most painful year either of us has ever lived through.

“Happily” may not be the right word, but “happier” definitely is. Having our diagnoses, even having our own individual medications, didn’t “solve” anything — but it gave us a new sense of perspective.

I still have the instinct to share my dazzling logic and reasoning structures (well, dazzling to me, anyway), especially when I feel I’m not being heard or understood.

And Natasha still finds that withdrawing from situations that are oversaturating her brain with stimulation and information is the most effective coping strategy.

But.

Now it’s more likely that when I get excited about sharing my thoughts, we’ll notice when I’m getting more emphatic — and she often can just hold up a finger or say “Could you slow it down, please?” This also has the side benefit of making me think about what I’m saying before I say it — which, believe it or not, does reduce the chance of me saying something wrong or that I might regret.

Likewise, if I see her becoming withdrawn — either during a conversation with me or even just out at a social event — my first thought is not longer “she’s ignoring me because she thinks I’m an idiot” or ”She hates this event!”.

Instead, I get a chance to try to be a good partner, and look around to find a way to reduce the chaos (especially if the cause of it is me).

In short, that particular kind of fight has almost completely disappeared from our life together. Which gives us the resources to meet other challenges more easily.

When people say ”Why bother with a diagnosis? I’m this many years old, and I’m doing fine, I don’t see what difference it would make?” I don’t argue. Everyone’s body (which includes the mind) is their own to do with as they like.

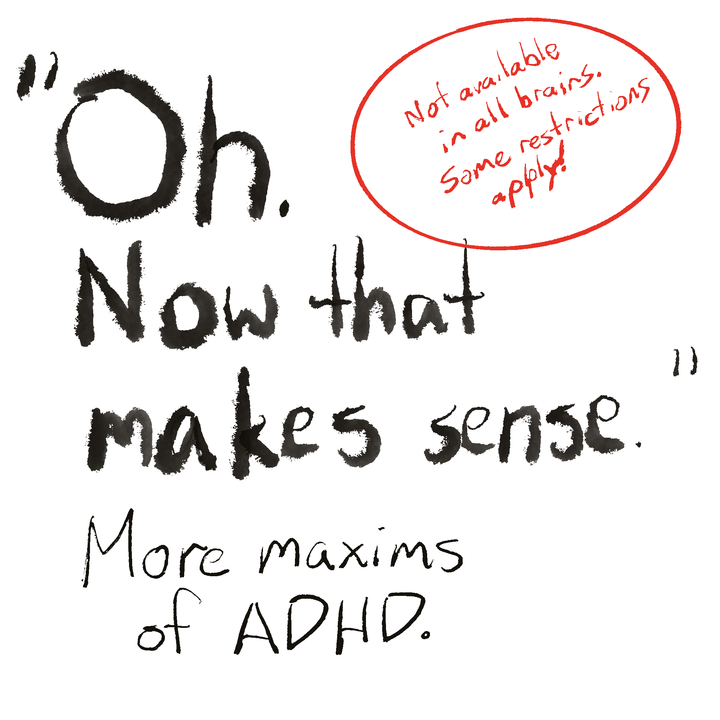

But I sure am glad we did it. Because while it doesn’t solve everything — it definitely makes a lot of things not so hard.

Comments ()